Tiffany Rose on Her Self-Published Book 'Pack Light: Poems, Prose and Untold Stories'

Tiffany Rose Smith's self-published debut book shines a light on sexual abuse and constructs a soft place for survivors to land.

This article references sexual assault and child abuse. Please take care and be mindful while reading. If you or someone you know has experienced any form of sexual abuse, contact the National Sexual Abuse Hotline at 1-800-656-4673.

I met Tiffany Rose Smith almost a decade ago when a mutual friend introduced us over email.

“Hey Tiff, meet Ashley. I think you two will vibe,” was the overall tone of his message. From that gracious first e-hello, a friendship took root in the way friendships tend to these days: a follow, a like, a DM, and some texts. Our version of going all the way was a four-hour Zoom call from our respective homes—she in Austin, Texas, and I in Brooklyn, New York.

Tiffany is a writer, and creative consultant, as well as a wife and mother of two boys. Like many Black women, she draws inspiration from Maya Angelou and Alice Walker, and truth-telling sits at the center of her creativity. So when Tiffany decided to write about what she calls “the terrible awful,” she knew the process would be metamorphic.

When Tiffany was 12 years old, her stepfather began molesting her. A few weeks after her 18th birthday, before leaving for college, his abuse escalated to rape, igniting the end of Tiffany’s silence and the beginning of her lifelong recovery. In Pack Light, she chronicles her experience through poetry, prose, and screenwriting to deconstruct the various truths of abuse and survival. With an uneasy story to tell, Tiffany resolved to do so on her terms.

One of the things I love about Pack Light is that it challenges my stupid assumptions about self-publishing.

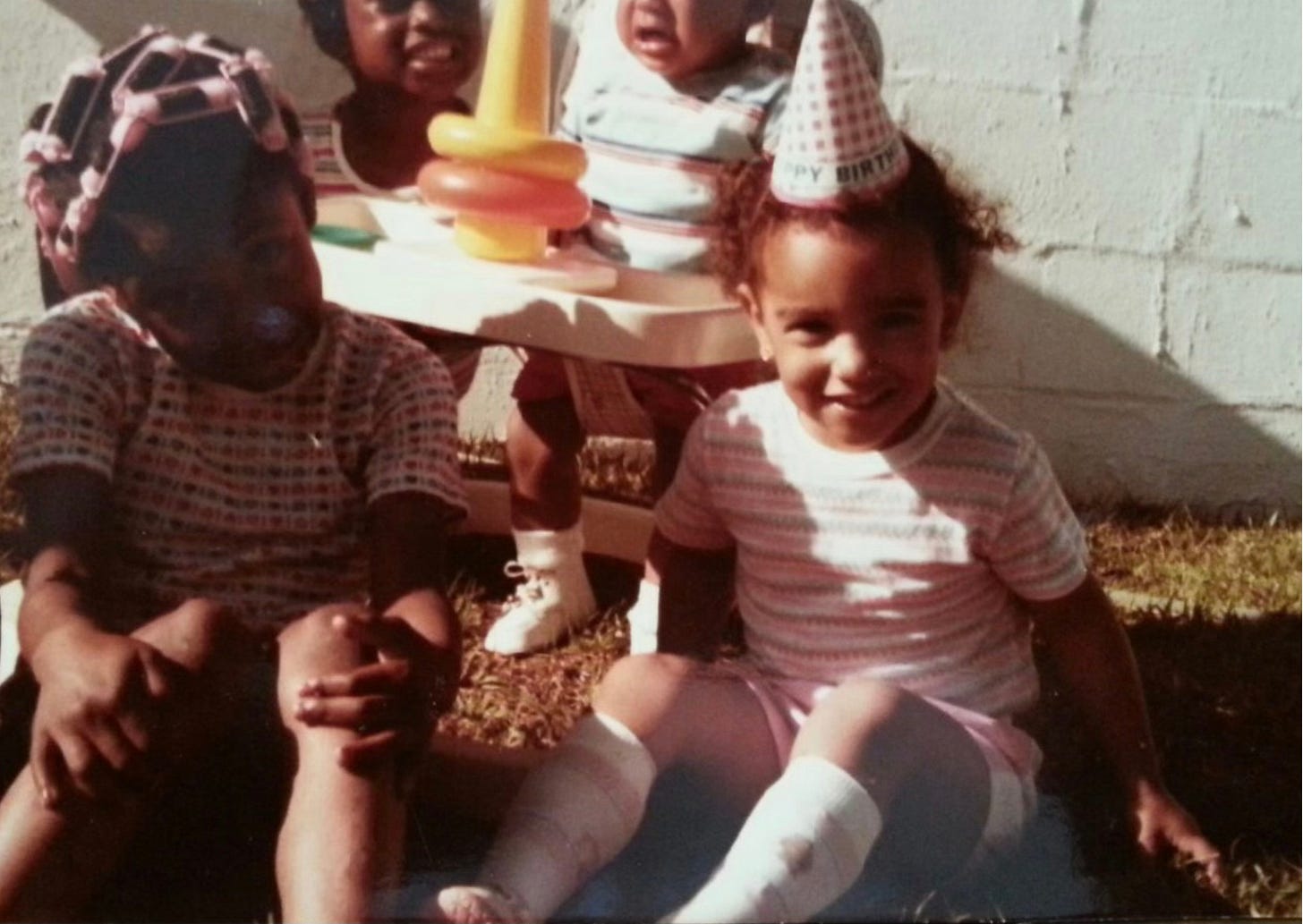

Last year, when Tiffany asked for my opinion on cover options, I thought she was soft-launching a book deal. This was no rushed effort; care was being put into the construction of her offering. There’s an unfussy white cover, a title in bold black lettering, and a Polaroid-style photo at the center. In the photo, a grinning five-year-old Tiffany is dressed in all pink, with a small kiss-lock purse in her hand.

Tiffany said the self-publishing process provided more autonomy and freedom but was far from the easy route. “I really struggled because, for me, it's like fifty percent the ‘aesthetic allergy’ to self-publishing,” said Tiffany, who learned a few vital lessons along the way. “I like to make beautiful things, and I have a very specific eye.” Even the back cover of Pack Light is marked with intention, featuring anonymous blurbs from Tiffany’s real-life friends.

“I wish I could’ve read this in college,” reads one blurb, “I wish I had this to read in my twenties and early thirties when I was first starting to heal. You are the new gift.”

There’s a reason why books like The Color Purple and I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings have been banned for decades. Both books contend with intra-familial sexual abuse or abuse that takes place in the family environment. Though the topic remains dangerously taboo, 90% of child abusers are someone known or related.

This kind of abuse is shrouded in shame and silence, which ultimately isolates victims and insulates predators.

This legacy of silence is exactly why stories — fictional or not — depicting survivors of sexual abuse hold significant importance to those who have lived it. For Tiffany, these stories were her lifeline. “I always tell people, if you want to know anything about me, my two favorite movies are The Wizard of Oz and The Color Purple. That's my identity right there.”

Watching the 1984 film adaptation of The Color Purple at the age of nine captivated Tiffany from the moment she heard the infamous opening line, “You better not tell nobody but God. It'd kill your mammy.”

Stories that unveil untellable truths about Black women became Tiffany’s guiding light from an early age because they gave language to the unspoken reality she lived every day. “There's something that is saving me over and over and over. And it is the knowing that there is a story on the other side of this.”

Tiffany, who wrote under the moniker "tiffany rose," started working on Pack Light during the pandemic. The sudden, involuntary hibernation brought up coping skills she hadn't resorted to in decades. “The COVID lockdown was wildly triggering for me. And [it] took me a minute to kind of understand what was happening, why I was so freaked out, aside from just the collective freak out. It just felt familiar to me in a way that made me go exploring a bit.”

Pack Light is broken down into three untitled acts. Act one visits Tiffany’s Floridian roots and the figureheads of her childhood — including her grandmother who she describes beautifully in a piece called “grandma got a compass for hands” which reads in part:

grandma gives directions the same way she cooks no measurements or mile markers just memory and knowing in her bones

Act Two parcels into different sides of the same story, reflecting the way abuse survivors feel split between two worlds—the one in which they are victims and the one in which they are individuals. For this reason, Tiffany split Act Two into "A Story" and "B Story." The "A Story" zooms in on what her home life felt like, while the "B Story" recounts Tiffany’s small-town girlhood which was marred by her stepfather’s abuse.

During our conversation, Tiffany and I discussed virginity, a topic I wrote about in a 2015 essay questioning purity politics. In an untitled piece, Tiffany challenges the narrow concept of virginity which undermines young survivors living in silence:

being a “virgin” has never meant more

than knowing the difference

between being a “good girl”and being good, girl.By calling out the clash between victimhood and personhood, Tiffany’s book implicitly challenges the model of perfection that preserves justice for those society deems innocent enough to be victimized.

In the final twenty-seven pages of Pack Light, Act 3 dives into love, self, God, and religion through the awkward lens of healing. It is the much-needed aftercare for those navigating recovery from any wound, especially the wounds of sexual abuse. The writing makes space for difficult, true, and multilateral realities of healing, including the painfully alienating walls built for protection.

torn petals

dulled thorns

and bruised buds

a flower still makes

a rose is still a rose

even when it

stops blooming

for safety reasons Despite its minimalist appearance and unassuming title, Tiffany’s book is anything but “light.” Drawn from the lyrics by the patron saint Badu, it reminds us to let go of the things we don’t need. “You can't hurry up ‘cause you got too much stuff,” Tiffany said, reciting the famous line.

“If I can do this, even if writing isn't your thing, find a bag and put your shit in it.”

While anyone can read Pack Light to get lost in the wordplay and gritty unconventional storytelling, Tiffany had a specific audience in mind. “I'll never not be writing about survival,” she said. “I'll never not be writing to survivors. That is my lens, that is who I am, that is what I do, and that is who I speak to.”

This was one of those reads that slows you down so you can pause, and settle in the moment. I am never not in awe of us, black women and black women writers who, even when few others are looking, see us, and see us through.